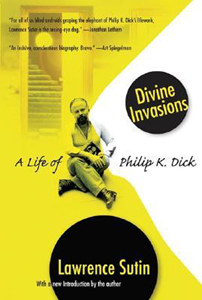

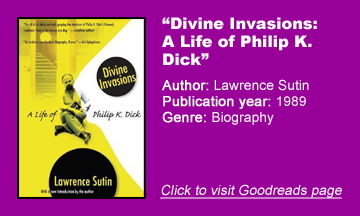

Beware before you crack open Lawrence Sutin’s “Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick” (1989). It’s considered the elite PKD biography for good reason: Sutin answers every question that’s answerable about Dick. He kind of kills the mystery. (But give it time and then pick up a PKD novel again – it’ll come back.)

Courtships and breakups

Sutin takes us through every relationship of “serial monogamist” PKD’s life to the point where we know the details of the courtships and breakups. We follow Dick (1928-82) to all of his Bay Area addresses, along with his foray to Vancouver and his later-life stops in Southern California.

This is page-turning stuff on par with a PKD novel, except it’s written in sober journalistic style because Sutin does not need to move this into a dystopian future with gee-wiz technology to glean entertainment value.

That said (and this is inevitable in a thorough biography), the 352-page “Divine Invasions” shrinks the world a bit. I love learning the real-life counterparts to fictional characters, but that knowledge does diminish my belief in PKD’s imagination – like “George Lucas in Love” does in regard to the “Star Wars” creator.

For instance, Bishop Timothy Archer from PKD’s last-written novel, “The Transmigration of Timothy Archer,” is based on his friend Bishop James A. Pike. Not just in terms of his name, but in terms of Archer’s journey: Pike also died in the Dead Sea Desert while searching for pre-Jesus documents with New Testament content.

He wrote what he knew

I hear the advice “write what you know” and think “But what about authors with wild imaginations, like PKD?” And yet PKD always wrote what he knew. His female leads are all based on his current or past wives, lovers and platonic female friends he longed for (PKD was married five times, and had several partners in the gaps between).

Or more accurately, his perceptions of them – depending on if he is being charitable or nasty.

Yet his twin sister Jane, who died in infancy, was always the most important woman in his life, and the real person most used as a model for his adult characters (even though, yes, it’s impossible).

And his homes are often the homes in his novels. Sutin doesn’t even use the phrase “based on.” The country home of “Confessions of a Crap Artist” is in Point Reyes; the “break-in home” of “A Scanner Darkly” is in Santa Venetia. The former is hard to heat because it’s on a concrete slab in both book and reality; the latter is broken into by unknown vandals in both book and reality.

Digging into the ‘Exegesis’

“Divine Invasions” was of particular worth upon its 1989 publication because Sutin had access to unpublished works. For the purposes of insight into PKD’s mind in his last decade, the most important is the “Exegesis,” his religious-theory journaling, which was published in 2011.

Always fair to both sides of a story (ex-wives Kleo, Anne, Nancy and Tessa are thoroughly quoted), Sutin examines the notion that PKD was crazy and the alternate theory that he was as sane as anyone else.

Through the “Exegesis” and Dick’s piles of letters to friends, the biographer makes a strong case that PKD was a sane (if obsessive) man interested in learning if there was any substance to his February-March 1974 visions from God (?) and a handful of later visions.

In retrospect, now that I know how biographical the novel is, PKD himself – through the surrogate of Angel Archer — concludes he’s sane in “Transmigration.” The mythology of Dick being crazy or drug-addled was partly encouraged by PKD himself, and he never discounted it, but nearly all of the friends and family interviewed by Sutin categorize Dick as sane.

PKD also believed he was doing his best writing later in his career, and he was proud of himself for taking Ursula Le Guin’s advice and developing a well-rounded female protagonist in “Transmigration.”

Both are fair self-assessments: His later books — if not strictly his best — feature his cleanest prose while tackling complex religious theories, and it was a big step for him to use a female POV character from start to finish. (Still, Mary Anne from “Mary and the Giant,” written back in 1954, shouldn’t be dismissed.)

The most important then-unpublished source for “Divine Invasions” is the “Exegesis,” but more drool-worthy for PKD nerds in 1989 would’ve been Sutin’s access to “Gather Yourselves Together” and “Voices from the Street,” eventually published in 1994 and 2007.

Critiquing the books

Sutin waxes about Dick’s most famous novels and stories in the main text, but he hits on all of the novels and some of the stories in an appendix. Sutin is a less generous critic than I am, finding little literary worth in those last two published novels (which are also PKD’s first two written novels).

On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being the lowest ebb of PKD’s talents, he says “Gather” isn’t worth grading, and “Voices” earns a 2. (Ouch. But at least they were published eventually, and we can judge for ourselves.)

Also serving as gold dust for completists, Sutin shares what little is known about PKD’s forever-lost manuscripts. Of these, several sound like they were reworked into other novels, such as “A Time for George Stavros” being absorbed into “Humpty Dumpty in Oakland.”

So that makes my sadness over their loss hurt a little less. (Although the “Scanner Darkly”-inspiring break-in alludes to stolen manuscripts, Sutin – and comments straight from Dick – make no mention of any of the “lost” novels being stolen in this break-in.)

Sad, fascinating portrait

“Divine Invasions” is not merely catnip to amateur PKD literary scholars; it’s ultimately a sad portrait of a fascinatingly troubled human being. Dick brought joy and pain to his family and friends, joy to his readers, and mostly pain to himself.

Sutin concludes his narrative beautifully, noting that Phil was able to smile at his visitors (but not talk) in the final hospital visits before his death from a series of strokes.

Coming on the heels of Dick’s 2-3-74 obsession, his comments about looming death and his lifelong connection with the sister he never knew on the mortal plane, Sutin’s last line is worthy of goosebumps: “Buried beside him is sister Jane.”

When thinking about Dick dying at age 53, I selfishly think of the novels we were robbed of — if he had taken care of his health, he could still be writing today. But “Divine Invasions” makes it clear that we got the PKD we got because he was who he was.

His messed-up psyche and life events allowed for his gloriously messed-up novels and stories in a more direct way than I would’ve guessed.