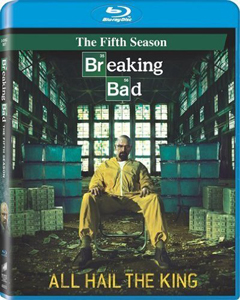

Over six Sundays, we’re looking back at the five seasons (and one movie) of one of the last decade’s elite TV series: AMC’s “Breaking Bad.” Next up is Season 5 (2012-13):

The new most-famous Heisenberg

I typed “Heisenberg” into a Google search to find out if there’s a deeper meaning to Walter White (Bryan Cranston) being nicknamed after the famous scientist. In confirmation that “Breaking Bad” is a dominant cultural force, there are more “BB”-themed results than there are about good ole Werner.

In addition to both Heisenbergs being physicists, both are associated with “uncertainty principles,” and for Walter, uncertainty bubbles up in the final season soon after his most assertive moment.

“You’re Heisenberg,” a lower-tier meth dealer says at Walter’s prompting in “Say My Name” (episode 7). “You’re god damn right I am,” Walter replies. A central pleasure of Vince Gilligan’s masterpiece – which closes with a 16-episode season spread over two years – is watching Walter become self-confident.

There’s never any question he’s doing this for his family – to leave them millions in cash rather than unpayable hospital bills – but the series finale, “Felina,” confirms a second motivation: As Walter tells wife Skyler (Anna Gunn), he likes being the meth kingpin of the Southwest.

“Breaking Bad’s” not-so-buried subtext is that it gives a person self-worth and satisfaction to be successful at an enterprise.

Meth-making is illegal and therefore dangerous, but that only makes me admire all the more Walter’s ability to navigate the costs of doing business – from money laundering (via the car wash Skyler manages) to taking care of surprising problems (the uncertainty principle, if you’ll allow the metaphor).

Crossing a line

Season 5 reminds me of “Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith” in that – like Anakin Skywalker — Walter crosses a line he can’t come back from. But unlike a grand space opera, “Breaking Bad” is grounded; Walter’s humanity shines through, especially when he’s desperate. It’s not an issue of good and evil (although it’s arguably an issue of evil acts).

Walter is always good at heart. The issues are that 1, he can’t escape the law any longer, and 2, he can’t win back the trust of teenage son Walter Jr. (R.J. Mitte) – who tellingly goes by “Flynn” in the later episodes.

The first point is almost trivial, since Walter is going to die of cancer soon anyway. It’s the second point that’s so tragic. Of all the heart-wrenching moments in Season 5, the biggest might be when Walter sees his son for the last time, from a distance, through a dirty window.

Walter gets a last moment with infant daughter Holly, and with money-laundering partner Skyler, who is on the fence about whether she hates his guts. But not with the son who shares his name.

On the other hand, Walt does well by his surrogate son, Jesse (Aaron Paul), springing him from his captors so he can speed off to “El Camino” (the 2019 “Breaking Bad” movie). Jesse has a rock-bottom opinion of Walter, but at least he knows where Walter is coming from.

Season 5, like all pre-planned final seasons, is technically about locking things in place — embarrassingly, I was caught off guard by the finale’s hook-up to the pilot episode’s flash-forward of Walt’s 52nd birthday – but this is no rote exercise in completing a jigsaw puzzle.

An uncertain game

We are constantly reminded that meth manufacturing and selling is an uncertain game. As DEA agent Hank (Dean Norris) puts it in a flashback, it’s easy to make money and easier to lose it.

Walt has learned this over two years of his life. Money, always in cash form, plays a pivotal role; note the darkly funny images of Hank with his one last barrel of money as he flees from Albuquerque to New Hampshire.

One could go down a rabbit hole about what money means to good people and what it means to evil people. For example, Mike Ehrmantraut (Jonathan Banks) is terrifyingly good at his protector/hitman job, but he does it in order to leave a nest egg for his granddaughter.

So I think of him as a good person. And also as a badass. “Shut the f*** up and let me die in peace” is one hell of an exit line.

But what gives “Breaking Bad” its heart – especially when characters we’ve known for a long time start to perish – is the fact that many players in this game have big hearts.

Paul displays Jesse’s anguish not only when a loved one is killed (R.I.P. Andrea) but also when he is forced to kill someone; his offing of Gale a couple seasons back goes to the core of what makes him tick.

This business never sits right with Jesse, but Walt is able to make excuses. “It had to be done,” he’ll say. Skyler is between the two poles, and her inconsistency is why most viewers don’t like her.

Plemons shines again

As Todd, Jesse Plemons stands out in one of his three roles in a short span as a likable murderer; see also “Friday Night Lights” and “Fargo.” On those other shows, Plemons plays a normal dude in an abnormal situation, but on “BB” he’s a sociopath who alternates between brutally terrifying and almost lovably innocent.

It starts with the shocking conclusion to the nail-biting train-heist hour “Dead Freight” (5), when Todd guns down a boy passing by the job site on his motorbike. Todd illustrates that sociopathy – maybe even more so than intelligence — is a key trait for success in high-stakes drug-running. Rather than taking time to be troubled by his actions, Todd works toward advancement in a career he’s perfectly suited for.

In the midseason finale, “Gliding Over All” (8), Hank finds Walt’s poetry book – a gift from Gale – and realizes his own brother-in-law is Heisenberg. I don’t know if the writers intended this or if it’s my own bias, but I thought Hank might be conflicted and might question the merits of his own job.

I entertained the notion that “BB” had taken its eye off the ball of the wider Drug War theme by immediately jumping into “Hank versus Walt.” I mean, Hank suddenly hates a guy he loved before he knew about the side gig. The daggers he stares into Walt in the desert showdown in the suspense masterpiece “Ozymandias” (14) are almost as deadly as bullets.

While I’m not thrilled with Hank for taking this path, it makes sense as I think about it from Hank’s perspective (injuries, lies, embarrassments, etc.), and I can’t deny it leads to stunning brother-versus-brother drama. The clash of the two actual sisters – Skyler and Betsy Brandt’s Marie – gets somewhat short shrift, although it’s not completely skimmed over.

Crazy-good Cranston

There’s almost never a case where Gilligan and his writers leave something good in the dust for a lesser storyline. Put the camera on Cranston, and I never wish I was watching the drama going on elsewhere.

You’re god damn right he’s Heisenberg, yet he never stops being Walter, as a small moment in “Granite State” (15) reminds us. Ed (Robert Forster), the man being paid to hide Walt in New Hampshire, makes his monthly delivery of supplies, and then Walt pays him another $10K to stay for an hour and play cards.

The sick man’s loneliness is as sad as any of the deaths because it underscores the tragic tale of Walter White: He was the best in the world at his specific job, yet he was never cut out for it.