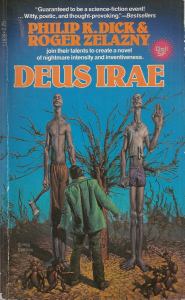

Philip K. Dick’s “Deus Irae” – co-penned with Roger Zelazny (1937-95) — was published in 1976, the decade when he released most of his religious-themed novels. But he started writing it in 1964, making it one of his earliest full-on explorations of the topic.

Also in 1964, Dick wrote “The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch” (published in ’65). Both books feature an evil deity, but whereas the dark god hangs over “Stigmata’s” events like a cloud, it’s the whole point of “Deus Irae.”

Focus on faith

Rather than an instance of Dick fumbling with questions he’d later articulate better, a case could be made that this is his best book that’s entirely about religion. (“Radio Free Albemuth” is my favorite PKD book about religion, but it’s also about many other things.)

“Deus Irae” (1976)

Authors: Philip K. Dick and Roger Zelazny

Genres: Science fiction, religious drama

Setting: Western wasteland after World War III

Like “Dr. Bloodmoney” (1963), “Deus Irae” is set in the wasted landscape of the Western states after World War III. In an undated near future, it chronicles two men’s search for religious answers. Tibor McMasters is a phocomelus: He has no limbs and uses a motorized cart, and he’s called an “inc,” for “incomplete.”

He goes on a Pilg (pilgrimage) from Utah to Idaho in search of the God of Wrath, Carleton Lufteufel, in order to take his photograph and then paint a portrait for his church.

The Servants of Wrath have surpassed Christianity – as represented by Pete, who follows Tibor to watch, stop or protect him (he’s undecided) — as the most popular religion in the West. Although “Deus Irae” doesn’t have a humorous tone, Dick and Zelazny are making a broadly dark-comedic observation about how humans side with winners – even if the winners are responsible for the destruction of the world. (See also “Beneath the Planet of the Apes,” from 1970.)

Dr. Bloodmoney had his followers, and Lufteufel – the bomb-dropper in this novel – has a whole religion in his name during his mortal lifetime. And in an Eldritch parallel, Lufteufel has scars, in this case administered by himself because he’s crazy.

Humanity’s destinies

The authors don’t posit that humanity is a victim of one crazy man; rather, they suggest that humanity is destined to produce such a person, humanity is destined to produce states, and states are destined to produce civilization-destroying bombs.

It’s the natural cycle of the human race, as the bounty hunter Schuld outlines when summing up the endgame of World War III to the traveling Tibor in chapter 15:

The wrath descended. Sin, guilt, and retribution? The manic psychoses of those entities were referred to as states, institutions, systems – the powers, the thrones, the dominations – the things that perpetually merge with men and emerge from them? Our darkness, externalized and visible? However you look upon these matters, the critical point was reached. The wrath descended. The good, the evil, the beautiful, the dark, the cities, the country – the entire world – all were mirrored for an instant in an upraised blade.

But “Deus Irae” doesn’t place the blame on any individual rational human. It blames Lufteufel, who is alternately portrayed as hopelessly insane, a preternaturally skilled trickster, or a god.

Innocent mutants

Tibor and Pete are particularly portrayed as innocents. Indeed, the post-war mutants who have sprung off Homo sapiens (a classic example of PKD showing a faster evolutionary process than exists in reality) don’t blame the individual humans they meet.

As with “Planet for Transients” (1953), the sentient lizards, bugs and rodents of this world are friendly. They serve as helpers on Tibor’s and Pete’s journey that could parallel “Alice in Wonderland” or “Lord of the Rings.”

Or any Campbellian hero’s journey — although in this case at least one of the “helpers,” Schuld, serves his own story, not that of our heroes. Schuld spices up the tale when he saves Pete from the Great C — a computer that eats people, as first introduced in its namesake short story from 1953.

However, Schuld is also an unnamed character who we have been reading about separately. The big reveal only works in the form of the written word, so if “Deus Irae” were to be adapted to the screen, a new way of presenting the twist would have to be devised.

Desire for meaning

Although this novel plays out under a satirical umbrella, it’s nonetheless a genuine exploration of man’s desire for meaning, spirituality and philosophical answers. It has an old-school religious vibe, with Tibor in particular seeking enlightenment through suffering; his journey via a cart pulled by a cow from Utah to Idaho is as perilous as one would assume.

Tibor, Pete, Schuld and Dr. Abernathy (the SOW church leader in Utah who commissions Tibor’s painting) are all searching and all chip in with observations and help for the others. “Deus Irae” is nominally a sweeping Good and Evil story, but it spends a lot of time examining the degree of goodness in each person. For example, the man behind the bomb isn’t evil; he’s mentally troubled.

We also see that Tibor’s awareness of his selfish reason for wanting to paint Lufteufel – the fame that comes with it – does not stop him from taking the assignment and then enjoying and cashing in on the fame. As SOW rises as the next dangerous and powerful force in the world, we must reconcile that good and meek Tibor is responsible for its ascension – and that he cares less and less as he gets older.

Dick and Zelazny are cynical toward religion, yet the book features a beautiful moment where a mentally challenged young woman, Alice, has her brain magically healed by the spirit of Lufteufel. The authors are of course taking humanity to task for the nuclear devastation of World War III (something assumed to be inevitable in the 1960s).

Absurdist comedy

But they aren’t all that thrilled with the pre-bomb world, either, as seen in their (well, OK, it’s pretty obvious this is Dick’s contribution) portrayal of an automated underground factory that has lost its (artificial) mind.

Granted, this is a damaged autofac, but I think PKD is poking fun at the entrenched nature of corporate producers of goods, even in times of peace. The autofac demands that customers treat it like a god, and it grabs Pete’s bicycle and returns a useless rain of pogo sticks.

“Deus Irae’s” most absurd moment comes when the autofac – located in the middle of nowhere by the reckoning of the post-bomb geography — produces a waiting room for Pete, who mindlessly reads an old Time magazine article about the search for a cancer cure. Regardless of one’s view of big business, we can all relate to the low-level frustration of hoping for good customer service while accepting mediocre service.

“Deus Irae” boasts an unusually focused plot from PKD – which makes me want to credit Zelazny for this aspect – with no dropped threads and no random turns in new directions. Despite chronicling a physically challenged man’s likely doomed quest to find God amid a post-apocalyptic wasteland, it’s engaging and energetic.

The expected usual blasts of absurdity from PKD don’t come with regularity, but “Deus Irae” is satisfying as a spiritual quest.

thank you for this wonderful review

Thanks for reading and commenting!