I remember disliking “The Man in the High Castle” (1962) on my first read, and the Amazon Prime adaptation (2015-present) – so bleak that I’d have to increase my antidepressant dosage to keep watching – didn’t alter my view. But it did inspire me to give the book another shot, and I really liked it this time.

It must be one of Philip K. Dick’s most literary works – which is why the TV series is inspired by the book more so than adapting it – as it features nearly a dozen leads and offers its pleasures through subtle moments more so than big ones.

Bevy of characters

One benefit of the TV adaptation is that I picture the beautiful Alexa Davalos as Juliana Frink, a wild spirit who has run off to the Rocky Mountain States. PKD also chronicles her husband, Frank Frink, a Jewish jewelry maker plopped in San Francisco, in the Japanese-controlled Pacific States. Also in SF is antique- and trinket-shop owner Childan, who accepts jewelry on consignment from Frink and his partner, Ed, after a highly entertaining bargaining sequence.

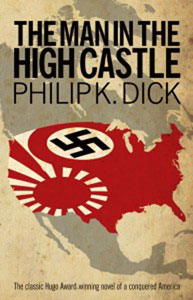

“The Man in the High Castle” (1962)

Author: Philip K. Dick

Genres: Alternate history, science fiction

Setting: San Francisco, 1962, with America ruled by the Germans and Japanese

The jewelry is a small point in the book, yet the pivotal one. It’s an oversight on the part of me and other “Buffy” fans that we don’t reference “Man in the High Castle” enough when talking about “The Wish” (Season 3, episode 8), where Giles smashes a pendant to go to an alternate reality that he suspects “has to be” better than the vampire-controlled Sunnydale he lives in.

In PKD’s novel, San Francisco official Mr. Tagomi meditates on a piece of Frink’s jewelry and finds himself in what we readers know as reality – the one where the Allies, not Japan and Germany, win World War II. (Interestingly, PKD himself would experience a spiritual vision of an alternate reality a decade later, which makes one wonder if it was a case of the cart leading the horse.)

Both “The Wish” and “MITHC” have the tricky task where the narrative thrust is to get these people from the bad alternate reality into the good real world, yet no one knows they are in the “wrong” reality. The trick up PKD’s sleeve is that the I Ching has become popular, coming over from Chinese tradition via the Japanese.

Sort of like tarot cards, this method purports to tell the truth about a person’s situation. Juliana uses the I Ching to determine that “The Grasshopper Lies Heavy” by Hawthorne Abendsen (a Salman Rushdie-type controversial novelist) is a truthful account of life after the Allies win the war.

The wrong reality

Juliana is wearing a Frink-produced pin at the time, which should be the key to entering that world, but PKD stops short of going there. I think this is more of a feature than a bug, though. Either Julianna will or won’t make the connection someday, but PKD has by this point made his point: There can be something intrinsically “right” or “wrong” about the reality you live in.

He also encourages us to think about how small (but still “right”) choices can bring us a step closer to the “right” reality; in this case, the steps that lead to Frink making the jewelry and distributing it, and then Childan, Tagomi and Juliana choosing to distribute it, meditate on it, or wear it.

A major difference between the TV series and book is the tone. In the novel, we know the Nazis and the Japanese rule the world and it’s horrific, but it doesn’t wallow in misery like the TV series does (in fact, PKD’s ruminations on the shifts in Nazi political power are engaging).

Rather, the Joe and Jill Schmoes in “MITHC” aren’t much different than those from his other works; they are doing their best to get by in the only world they know. There are no scenes of Japanese or Nazi officials murdering people, yet we know it is happening off page, and that’s enough.

Moments of understatement

PKD’s writing style here includes moments of understatement, wherein someone’s life-changing decision enters their mind with the same urgency as if they were making a grocery list. Juliana matter-of-factly murders her undercover-Nazi boyfriend, and later, Tagomi matter-of-factly decides to kill himself if he can’t get out of the alternate reality he witnesses via the jewelry.

At other times, small moments (to an outsider) are overwhelmingly important to the person experiencing it, like when the nervous and sweating Childan demands an apology from Paul, a powerful Japanese man who had insulted the jewelry.

PKD doesn’t write like other authors write, but he does illustrate the way people’s brains work: Huge moments in life come out of nowhere even as we overthink small issues. (Those small things matter too, PKD suggests, but in unpredictable ways.)

Changing language

PKD does one highly unusual thing in “MITHC.” He often writes in sentence fragments. I think this might be to mimic how English spoken by native Japanese people is often missing words, yet we understand what they are saying.

PKD might be illustrating how the English language is changing in the Pacific States after the Japanese takeover. At first blush, this should make “MITHC” hard to read, but it does not; I had no trouble getting into the flow once I realized what the author was going for.

Ultimately, “The Man in the High Castle” is a masterpiece of world building. Yes, the world PKD builds is one where the Nazis and Japanese rule the Earth (and the Nazis are also expanding throughout the solar system, which is why this can be classified as sci-fi in addition to alternate history).

It’s hard to imagine a more bleak historic twist, yet “MITHC” isn’t as grim as I feared. There are plenty of troubled folks moving this story along, but when you’re reading a book so intensely about people – and not so much their evil controlling institutions – even the bleakest material can flow smoothly.