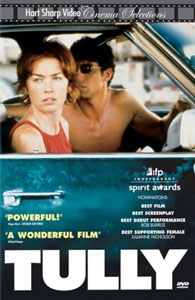

The Diablo Cody/Jason Reitman “Tully” – now available for home viewing – eventually won me over by being a quality film, but I was initially peeved that it uses the same title as one of the best pictures of 2002. But on the other hand, maybe this new “Tully” will draw fresh attention to the original “Tully,” which has become a forgotten gem in part because it was never a major release to begin with and in part because a lot of its talent didn’t attain the spotlight they should have.

Directed by Hilary Birmingham and co-written by Birmingham and Matt Drake (based on a short story by Tom McNeal), “Tully” is about a farmer and his two sons in Nebraska. It has a more rural “American Graffiti” vibe as it tells the threshold story for the Coates brothers — Tully Jr. (Anson Mount) and Earl (Glenn Fitzgerald), young adults who will soon be adults, whether they want to be or not.

Tully Jr. is a ladies’ man – and it’s easy to see why, with Mount’s movie-star looks – but a good-hearted one. Earl likes to lose himself in the movies at the nearby one-screen cinema, and he’s awkward around girls, except his best friend, Ella (Julianne Nicholson), who regularly rides her bike the two miles over to the Tully farm.

The plot, such as it is, swirls around Tully Russell Coates Sr. (Bob Burns). This simple, kindly man had brought his boys up to this Cornhusker State farm from Kansas 15 years ago, after the death of his wife. But now, despite his rigid adherence to a working routine and regular bill payments, the bank aims to foreclose his farm for mysterious financial reasons.

“Tully” isn’t a plot-oriented film, though; it’s a character study. What’s so impressive is that it’s an equally fascinating study of each of the four people I mentioned above, all of whom are wonderfully acted. On my first viewing, I connected with Earl because of his shyness and awkwardness. But on this viewing, it’s clear to me why Tully Jr. is the title character; it’s fascinating how at every turn he dodges the ladies-man stereotype he is supposed to fit.

Ella is cute in a girl-next-farm-over way, yet she’s authoring her own story. And Tully Sr. is a case study in the quiet heroism of unselfishness, even as he is gently teased by corner-store cashier Claire (Natalie Canerday) for buying a six-pack of beer every Friday evening like clockwork.

Filmed in Nebraska and Iowa, “Tully” is a moving postcard of farm fields and small towns without being Earth porn. At one point, Tully Sr. takes a moment to admire the view; it’s just a field and unbroken blue sky, but those of us who have lived in the Midwest know where he’s coming from. Later, Ella tells Tully Jr. it’s getting cold out, a reference to the coming change of seasons that works as a metaphor for the changing “season” of their lives. Birmingham is rarely heavy-handed; she lets the fields and sky wash over a viewer.

And she employs that same trick with her characters. The greatest strength of “Tully” is how a viewer gets caught up in these four people’s lives without knowing exactly why. In part, it’s because of the great acting. But even in good films, we often know the structure, arc and genre; for example, “Eighth Grade” is a coming-of-age story. “Tully” can of course be rigidly defined after we absorb it, if we so desire. But during the moment, it’s more about four real, layered people than just about any other scripted film I’ve seen.

I made an “American Graffiti” parallel earlier, but that’s just for the sake of a starting point. These characters are all a bit older than high school seniors. Their ages aren’t strictly defined, but the three young actors are well into their 20s. “Tully” gives me the sense that farming and small-town life means that you develop an adult work ethic very early but, by the same token, don’t set out to find your unique traits until later than a city kid might. Intentional or not, the casting of slightly older actors for a threshold journey beautifully meshes with “Tully’s” meditations on the stillness of routine and the inexorable passing of time.

Adding to the poignancy of “Tully” is the rather frustrating fact that, rather than being a career-launching calling card for her, Birmingham has made zero scripted films in the 16 years since. Drake likewise has a thin IMDB resume. Burrus died in 2007, and has to be on the short list of greatest one-performance wonders in film history.

The younger actors are a little more in the spotlight: Nicholson, Fitzgerald and Mount work steadily, and the latter is especially enjoying a resurgence, having been cast as Captain Pike in the upcoming Season 2 of “Star Trek: Discovery.” Still, the most recognizable face in “Tully” might actually be John Diehl in a small role; he had a strong character-actor career before the film, and that has continued.

But “Tully” remains a special film for everyone who helped make it. It should’ve led to bigger stardom, yet it fits with the film’s theme that it did not. Even if it’s by accidentally purchasing the wrong movie online, I hope the Cody/Reitman “Tully” leads people to rediscover the wonderful original.