Disney is delving heavily into the dark side in its early “Star Wars” projects, from the novels “Tarkin” (2014) and “Lords of the Sith” (April) to the recently launched “Darth Vader” comic series that explores the Sith lord between Episodes IV and V. The old continuity, now known as Legends, trod similar ground in its final years, particularly with the four five-issue comic series under the “Darth Vader” banner.

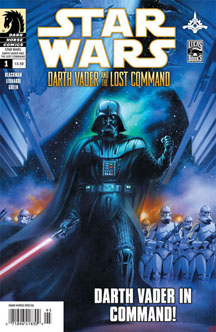

Unlike Marvel’s “Darth Vader,” Dark Horse’s “Darth Vader” explores the character right after “Revenge of the Sith,” when Palpatine’s Empire is held together by citizens’ fear of the Emperor and the iron fist of his primary enforcer. While authors delved into the head of Darth Vader as soon as the main beats of his backstory were completed in 2005 (I believe Karen Traviss’ short story “A Two-Edged Sword” was the first story from Vader’s POV), Haden Blackman delivered one of the most daring tales with “Darth Vader and the Lost Command” (2011).

I always liked Steve Perry’s “Shadows of the Empire” revelation that the dark side keeps Vader alive – so much so that when he experiences happiness about healing his lungs with the Force, he immediately relapses because he has lost touch with the dark side. So it’s not simply that Vader has buried his past, as many people do if they’ve experienced traumatic events, but rather that he will literally die if he thinks happy thoughts. At the same time, his thoughts of Padme keep him focused, whereas if he were totally to give himself to the dark side, he’d lose all sense of himself.

Blackman continues with this idea, as “Lost Command” opens with strikingly contradictory images. Vader dreams of a life that could have been with Padme: They have a son named Jinn, and Anakin goes on missions wiping out the last of the Sith while Padme serves as supreme chancellor. But in reality, the “neural links” to Vader’s machine parts are being reset, and it’s so physically painful that he dreams of this false reality to “keep me sane.”

Just as the Emperor values Vader’s anger – and often provokes it – he believes the third most powerful man in the galaxy, Grand Moff Tarkin, will also be a better servant if he’s angry. So in classic Palpatine fashion, he sends Vader to secretly kill Tarkin’s son, Garoche, while also taking out some enemies of the Empire. (This element of Tarkin’s story wasn’t continued in Legends canon, nor was it carried over to Disney canon. Wookieepedia tells me Garoche’s mom is Thalassa Tarkin, from Russ Manning’s newspaper strip story “Princess Leia, Imperial Servant,” but that’s not mentioned in the story.)

“Lost Command” is peppered with Vader’s visions of Padme, along with awesome shots of him fighting without his helmet on. All told, the pitch-black tragedy of this character seeps into the reader’s psyche.

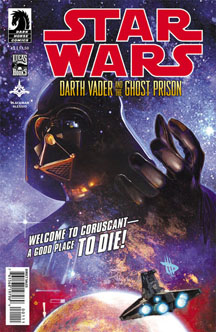

A more common type of Vader tale comes in Blackman’s “Darth Vader and the Ghost Prison”(2012). As if he doesn’t want to get quite so close to Vader again, the author tells this story from the perspective of Imperial officer Laurita Tohm, a recent graduate of the Academy. Tohm gets a close-up view of Vader’s actions, making “Ghost Prison” similar to many Vader stories in other series, notably “Empire,” “Rebellion” and Brian Wood’s “Star Wars.” While “Ghost Prison’s” structure is familiar, it’s one of the elite stories in this subgenre, capped off by a final-page surprise that shouldn’t be surprising. (After all, Vader has never played well with others.)

Truth be told, Tohm’s headspace isn’t that much of a relief from Vader’s. Imperial Headmaster Gentis recruits an entire graduating class of cadets to join him in an open rebellion against Palpatine, whose warmongering has led to the deaths of so many of Gentis’ students. (That Gentis would be able to pull this off without being backstabbed by a single student is extremely unlikely. As history shows us, rebellions structured around small cells, guerilla tactics and secret codes – what the Rebel Alliance will do – are more likely to succeed.) Tohm stays loyal to the Emperor and Vader, though, and – in a nice tie-in to the “Empire” arc “Betrayal” – future Grand Moff Trachta is also along for the ride.

Blackman’s juicy idea of the title – reflecting the U.S. military’s Gitmo prison — is that the Jedi Order maintained a hidden prison for its most dangerous enemies during the Clone Wars. Vader (rather conveniently) finds a recording of a council meeting where Yoda says, “When this conflict ends, bring these criminals to trial we will. But while war rages, in our care they must remain.”

Often good at tying his stories into the wider saga (see “Jango Fett: Open Seasons”), Blackman references some Jedi from the “Clone Wars” saga when we meet the prisoners and learn how they were captured. It’s a missed opportunity to bring back some “Clone Wars” villains, but at least the Dark Jedi Shonn Volta – who can guide blaster bolts – is a good ally for Tohm.

Dark Horse’s “Darth Vader” comics are also a treasure trove for fans interested in vehicles, as we see the evolution of Imperial craft. For example, Vader flies in a V-wing, the predecessor of the TIE fighter. The Empire also uses LAATi gunships (from “Episode II”) and walkers (from “Episode V”). As “Lost Command” shows us, the latter don’t work as well in quicksand as they do in snow.