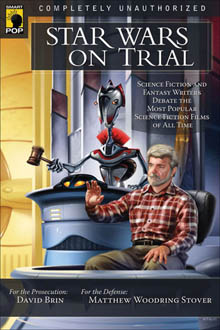

Here is the fourth and final part of my series inspired by Benbella Books’ “Star Wars on Trial”(2006), a collection of essays responding to eight charges against the “Star Wars” franchise. Sci-fi author David Brin, a critic of the prequels, was the prosecutor, and Matthew Stover, author of four “Star Wars” novels, represented the defense. Various essayists were the witnesses for each side …

CHARGE NO. 8: THE PLOT HOLES AND LOGICAL GAPS IN STAR WARS MAKE IT ILL-SUITED TO AN INTELLIGENT VIEWER.

This is the chapter of “Star Wars on Trial” I was most looking forward to, just because the geek in me finds plot holes, possible explanations and retcons entertaining (see my “X-Men” flashback blog posts from last month). But it’s the most disappointing part of the book as Prosecution witness Nick Mamatas doesn’t mount much of a case at all, instead equating “Star Wars” fans with hogs at a trough.

Don DeBrandt’s defense is that plot holes and logic in “Star Wars” don’t matter. He points out that holes in the narrative are filled by children’s imaginations, and I can attest that he’s right. As a kid, I spent hours dreaming of possible stories in the “Star Wars” universe, either with action figures or an ancient version of WordPerfect. As an adult, I read and re-read EU stories, and think about how the grand story fits together. In many ways, the fact that the “Star Wars” films don’t explain every little thing is exactly the point.

Still, I wished the witnesses would’ve debated some substantial plot holes. Mamatas mainly has a problem with the parody-ready plot conveniences, such as the Death Star basically having a bulls-eye on it. But there are plenty of real-world examples of governments designing things in sloppy fashion. Indeed, most tragedies in failure of design or planning by governments – particularly imperial ones — are not portrayed on film because they are so mundane. But it doesn’t even have to be something designed by a government. One could argue that the 9/11 terrorists hit a lucky bulls-eye to get the buildings to collapse like that. Also, films always simplify things in order to make points about reality. While a thermal exhaust port that can blow up the station may not be likely, it only has to be plausible.

Mamatas also doesn’t like that Yoda and Obi-Wan keep information from Luke, and that it took Vader a while to find out about Luke. As I discussed in previous “Star Wars on Trial” charges, Obi-Wan and Yoda took a flawed approach to dealing with Luke and Leia. Their choices were not logical, but that doesn’t mean the films themselves are illogical. The demand that every character be perfect is ridiculous. What a boring film that would be.

The relative strengths of Force powers bothers Mamatas – for example, he wonders why Vader didn’t sense Leia’s Force powers when he tortured her. Answer: He wasn’t looking for Force powers, and Leia wasn’t aware of her potential powers and therefore did not tap into them. Irony is an element of storytelling, too. And besides, there are many examples that make it clear that Force skills require training and vigilance. It’s made up for the GFFA, sure, but it’s not magic. It has logic and rules behind it. Even the ability to live on as a Force spirit — something accomplished by Yoda, Obi-Wan and Anakin at the end of “Episode VI” – comes from training.

The essayist also wonders why Darth Vader doesn’t recognize C-3PO or R2-D2. Even a cursory glance at the Expanded Universe shows that protocol and astromech droids of those designs are common, but even without the EU, it can be inferred from the films themselves (for example, C-3PO meets a rude version of himself on Cloud City).

Under Charge 8, Brin also submits an exhibit listing plot and logic holes shared by fans in response to his Salon articles. OK, now we’re getting to the juicy part, right? Not quite. All of the bullet points are either demands for every little detail to be filled in (someone wants an explanation of the Separatists’ politics beyond what we got in “Episode II”), or questions that have simple, inferable answers (Why did Yoda grab the clone army if he was opposed to its existence? Convenience and necessity.).

These critics aren’t so much protesting plot holes as they are protesting the existence of layers in a sweeping narrative about galactic civil war. Sure, some of the narrative oddities are mistakes that have to be patched over with apologetics and EU novels, such as Lucas being wishy-washy on the Skywalker family tree over the course of film production. In other cases, it’s just a matter of what Lucas chose to emphasize in the two-hour film. We don’t see the Naboo prison camps, but we can imagine them (or at least, an engaged viewer can). A case could be made that “Episode I” would be better if we saw the concentration camps, but that’s not the same as a plot hole.

I was ready to tackle the common criticism that a parsec is a measure of distance, not time: A.C. Crispin explained the Kessel Run, and how space itself gets warped near black holes, in “The Han Solo Trilogy” nearly a decade before “Star Wars on Trial” came out. I was ready to take on even harder questions like why do Owen, Beru and Obi-Wan look 40 years older, instead of 20 years older, in “Episode IV”: Tatooine’s harsh twin suns make people age faster. John Jackson Miller’s “Kenobi” (2013) touched on this, but the theory became popular as far back as “Episode II’s” release.

But the Prosecution doesn’t give us anything challenging. The dumbest example from Brin’s list of fan-submitted logic flaws is the accusation that Anakin’s saber is blue in “Revenge of the Sith” and then it’s green in “A New Hope,” when Obi-Wan gives it to Luke. Forehead smack. I don’t need to tell “Star Wars” fans that it’s blue in both movies. Presumably this critic was thinking of Luke’s green saber in “Return of the Jedi,” and apparently Brin didn’t think too hard about what he put on this list.

And maybe that’s what it comes down to: Fandom, and caring enough to think about details. Throughout these essays, there are many more mistakes and examples of shallow understandings of the saga in the Prosecution essays than in the Defense essays. At one point, a couple of Brian Daley’s non-“Star Wars” novels are cited as “Star Wars” novels. And at least three times, Leigh Brackett is cited as an example of what “The Empire Strikes Back” did right, and therefore why it’s better than the other films – employing a screenwriter with a background as a sci-fi novelist. The problem is that Brackett died early in the writing process, almost all of her work was scrapped, and Lucas gave her a posthumous credit as a respectful gesture. Lucas wrote the story, director Irvin Kershner had a substantial role in shaping it, and Lawrence Kasdan polished the dialogue. “Star Wars” fans know this, casual fans and critics don’t.

How do you become a fan – rather than a cynic — in the first place? You had to first experience “Star Wars” as a kid. If you’re lucky enough to be one of those people, you automatically filled in narrative gaps with your imagination as a kid, and are probably still doing it today with each new “Star Wars” story. It’s harder for an adult to engage the imagination in the same way it’s harder to learn a language. George Lucas’ greatest gift to “Star Wars” fans is not that he gave us perfect films, but rather that he trained us to make logical inferences in a fictional world, even if it meant we had to use our imaginations to do so.

More “Star Wars on Trial” essays: (Part 1) (Part 2) (Part 3)