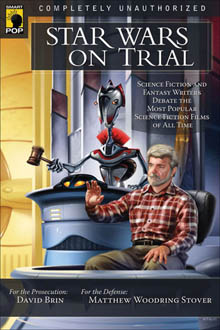

Here is the second installment in my series inspired by Benbella Books’ “Star Wars on Trial” (2006), a collection of essays responding to eight charges against the “Star Wars” franchise. Sci-fi author David Brin, a critic of the prequels, was the prosecutor, and Matthew Stover, author of four “Star Wars” novels, represented the defense. Various essayists were the witnesses for each side …

CHARGE NO. 3: STAR WARS NOVELS ARE POOR SUBSTITUTES FOR REAL SCIENCE FICTION AND ARE DRIVING REAL SF OFF THE SHELVES.

In “Star Wars on Trial,” the Prosecution and Defense both reference statistics showing that sci-fi novels don’t sell well. In 2004, sci-fi books ranked last among all genres. The Prosecution says the numbers are lower than they otherwise would be because of the negative influence of “Star Wars” novels, while the Defense says they are higher than they otherwise would be (and they point out that the “Star Wars” best-sellers subsidize other sci-fi novels at Del Rey). There’s no way for us to know if the glut of “Star Wars” novels leads to more or fewer non-“Star Wars” novels (a lower percentage, sure, but that’s beside the point since publishing is not a zero-sum game). There is no basis for comparison – we can’t go into an alternate reality that shows sci-fi book sales absent of the existence of “Star Wars.”

All we can do is look at anecdotal examples. I got into sci-fi via “Star Wars.” I’ve since gone on my requisite Clarke, Asimov and Heinlein kicks, and eventually discovered PKD, who is my favorite novelist, sci-fi or otherwise. I don’t think my example of “Star Wars” as a gateway drug to other sci-fi is unusual.

Although the notion of “Star Wars” as “substitutes” for other sci-fi is unprovable based on available statistics, let’s humor it for a moment in order to address the idea that these substitutes are “poor.” The roster of “Star Wars” novelists includes many sci-fi writers who are widely acknowledged for their talents, including Defense representative Stover. In her witness essay, Karen Traviss (who I rank as the best “Star Wars” novelist) says her “Star Wars: Republic Commando” series made her a better writer. “Episode II’s” establishment of the clone army allowed her to skip the set-up and get right into the juicy ethical dilemmas, and the tight deadlines of tie-in novels kept her from overthinking things and getting bogged down. It’s interesting to note that Traviss knew almost nothing about “Star Wars” when she got the assignment. And yet she still wrote brilliant “Star Wars” novels, which goes to show that the EU is a vast sandbox that has room for many kinds of sci-fi and many kinds of genres outside of sci-fi — in the case of Traviss, it was great military sci-fi writing along with thoughts on cloning ethics.

If Traviss – not to mention Stover, Zahn, Stackpole, Allston, Crispin and Daley — is a poor substitute for “real” sci-fi, then I fully admit that I don’t know what “real” sci-fi is. (And the definition of sci-fi will only get more confusing as each of these charges comes up.)

CHARGE NO. 4: SCIENCE FICTION FILMMAKING HAS BEEN REDUCED BY STAR WARS TO POORLY WRITTEN SPECIAL EFFECTS EXTRAVAGANZAS.

I think it’s legitimate to say that “Star Wars’ ” success in 1977 led to stupid special-effects blockbusters, yet my verdict is “not guilty” for two main reasons that aren’t specifically addressed in “Star Wars on Trial.” 1) George Lucas is an independent filmmaker. Not only did he have no say in what Hollywood – or even a specific studio — has done in the last three decades, he has been anti-Hollywood his whole career. One example is his withdrawal from the Directors’ Guild after being fined for putting the credits at the end of “The Empire Strikes Back” rather than the beginning. That gave him a thinner pool of directors to choose from on “Return of the Jedi,” but he put his principles first. Along these same lines, while it’s legitimate to criticize Lucas’ films on their merits, it’s unfair to criticize him for his films being successful and therefore influencing short-sighted Hollywood studios. Although Lucas doesn’t apologize for his films’ success (nor should he), he actually has no control over their success. No one is forced to buy tickets to “Star Wars” films – indeed, with the rising cost of movie tickets, one could argue people are discouraged to buy tickets.

And 2) Imagine if all special effect extravaganzas were as good as the median level of a “Star Wars” film (which I guess would be “Return of the Jedi”). If that were the case, we wouldn’t be complaining. As it stands, the high-profile blockbusters that we complain about are much worse than an average “Star Wars” film, and arguably even worse than the worst “Star Wars” film –compare the thematic and character depth of a “Star Wars” film to a “Transformers” film, for example. Even the Prosecution essayists in “Star Wars on Trial” note that the earliest “Star Wars” knockoffs – “The Black Hole,” “Star Trek: The Motion Picture,” TV’s “Battlestar Galactica” – fell well short of the high bar set by “Star Wars.” It’s absurd to say “Star Wars” — and not the knock-offs themselves — bears blame for that.

CHARGE NO. 5: STAR WARS HAS DUMBED DOWN THE PERCEPTION OF SCIENCE FICTION IN THE POPULAR IMAGINATION.

On this charge, I can pretty much repeat my defense from Charge 4, which contends that “Star Wars” led to worse blockbuster movies. In short, Lucas can’t control what other people do. But this charge is even more off-base — it suggests he has control over what people think — in addition to being vague. It’s hard to define what we’re arguing about here.

First off, who says “Star Wars” belongs in the science fiction category more so than in any other category? Genre categorizations can be traced to the traditions of the bookstore shelving system, which influenced video-store shelving, and today, digital-streaming categorization. Lucas certainly didn’t make the decision. He knows what a straight-down-the-middle sci-fi film looks like: He made “THX-1138.” But he intended “Star Wars” to be a hodgepodge of genres, and it is: The films combine elements of Westerns, Japanese samurai films, mysticism, political parable, technological predictions, Air Force war movies, classical music, Ralph McQuarrie paintings, and soft sci-fi serials (as opposed to hard sci-fi, which takes the laws of nature seriously; although “Star Wars” also has elements of Asimov’s “Foundation” series, which leans toward hard sci-fi).

Long before “Star Wars,” the genre categorization system decided to put space operas in the vein of “Star Wars” under “sci-fi/fantasy” rather than other potential categories such as “Western.” They decided that the elements of space travel and other technological innovations trumped the other elements. And that’s fine. I have no problem with the idea of genres for the sake of organization.

I think it’s fair to say that “Star Wars’ ” categorization as sci-fi leads an Average Joe to associate sci-fi with “Star Wars” – although this was truer in the past than it is today. Prosecution witness Tanya Huff nicely demonstrates this through an anecdote: In 1980, she was crossing the Canada-U.S. border to attend a sci-fi convention in Boston. The border guard didn’t know what she and her fellow colleagues were talking about until one of them said “You know, like ‘Star Wars.’ ” But what Huff doesn’t emphasize is that the anecdote also demonstrates that the Average Joe wouldn’t know sci-fi at all if not for “Star Wars.”

Furthermore, since 1977, there have been a lot of good and popular sci-fi films of all types. Some of them are in the vein of “Star Wars,” but most aren’t. Most good sci-fi films (even some of my favorites, like “Alien,” “The Terminator” and “Jurassic Park”) tend toward future predictions and cautionary tales more so than space opera. And stylistically, not much sci-fi looks like “Star Wars,” with its lived-in future. The pre-“Star Wars” template of shiny future tech is still more influential on sci-fi films, except in dystopian films, and those stand apart from “Star Wars” on thematic grounds. The closest imitator to “Star Wars” on all counts is TV’s “Firefly,” which is rarely accused of being dumb.

I’m struggling with what “dumbed-down” means because I don’t think “Star Wars” is a dumb film series. Flawed in execution at times, but too filled with important ideas to be called dumb. In fact, if it spelled out all of the concepts that the Prosecution charges are poorly defined (for example, if a character gave a monologue explaining that the queen of Naboo was elected rather than appointed by succession), it would be in danger of treating the audience as dumb. Certainly, there exist genuinely dumb films that make no sense on any level, but to lump “Star Wars” in with those is intellectually lazy.

Even if the popular imagination did see “Star Wars” as the be-all, end-all of sci-fi – which I think is less and less the case as time goes by — that would be a sad reflection on the popular imagination. It would not be the fault of “Star Wars,” which encourages people to think for themselves and not merely accept what is popular (such as the popularly elected Chancellor Palpatine, or the traditional notion of Jedi as flawless opinion leaders).

CHARGE NO. 6: STAR WARS PRETENDS TO BE SCIENCE FICTION BUT IS REALLY FANTASY.

First off, “Star Wars” never pretended to be ONLY science fiction. A quick perusal of any book or documentary on Lucas’ creation of “Star Wars” shows that his influences ranged far beyond science fiction. Although some have accused Lucas of historical revisionism in interviews (for example, some are rightly skeptical of the idea that he was locked into the Skywalker family tree before he began shooting “A New Hope”), he has consistently been open about his influences: Westerns, Japanese samurai films, Air Force war movies, “Flash Gordon” serials, fantasy like “Lord of the Rings” and science fiction like “Metropolis.”

Second, “Star Wars” doesn’t have to pretend to be science fiction, because it IS science fiction. At the same time, it doesn’t hide the fact that it has elements of fantasy.

There are a couple of great essays in “Star Wars on Trial” on Charge 6. Prosecution witness Ken Wharton introduces several exhibits from Lucas interviews and the films themselves showing that “Star Wars” is fantasy. He says the one element of science fiction, the midichlorians, is the exception that proves the rule. By the time I was done reading his essay, I was convinced that “Star Wars” is fantasy, not sci-fi. Defense witness Adam Roberts contends that “Star Wars” is a comedy in the Shakespearean sense and fantasies are dramas in the Shakespearean sense. Also, since no one is kicking “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” (a comedy in both the Shakespearean and modern sense) out of sci-fi, “Star Wars” doesn’t deserve to be kicked out either. By the end of his essay, I was convinced “Star Wars” is sci-fi, not fantasy.

Can a story be both sci-fi and fantasy and still make sense? Brin argues that the two genres are opposites and therefore incompatible: Sci-fi is about improving society, whereas fantasy values traditionalism. Wharton also says the genres are opposites, but for a different reason: Sci-fi asks why, fantasy does not ask why. Wharton argues that a good story doesn’t mix the two genres, because that would lead to confusion about the rules of the game. I contend that this should have been the wording of Charge 6: “Star Wars’ mix of sci-fi and fantasy leads to a confusing narrative.”

At first glance, “Star Wars” does mix sci-fi and fantasy, “why” and “whatever,” but further exploration reveals that the saga answers most of the questions that initially seem fantastical, and therefore leans toward sci-fi. Why can Yoda lift that X-wing with the Force? Midichlorians. Why did Obi-Wan, Anakin and Palpatine get thrown in a specific direction in the crashing starliner in “Revenge of the Sith,” when the laws of nature suggest they should be in zero-G? Stover’s novelization provides an explanation.

On the other hand, there are exceptions that are never answered in the films or the Expanded Universe, or even by fans writing apologetics essays. Why is there sound in space? Why do spaceships move as if they are in an atmosphere? The answer to these questions is that it looks and sounds cool. But while that is a flippant response, I don’t think “Star Wars” hurts kids with its inaccurate science. “Star Wars” can be their entry point to science studies, where they then learn the reality of natural laws. Nor does it hurt the overall story. We don’t know why there’s sound in space or why spaceships move like they’re in an atmosphere, but “Star Wars” answers enough other questions that we can live with a couple mysteries.

Under the widest definition (and even unique definitions, like Brin’s, because “Star Wars” includes both traditionalism and a longing for things to get better), “Star Wars” encompasses both sci-fi and fantasy. But that doesn’t mean the storytelling falls apart.

For example, TV’s “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” tells sci-fi stories (a teen, and later the government, builds a Frankenstein’s monster), and it also features magic that violates the laws of nature. It’s not a narrative problem as long as the rules of the game are clear to the audience. As viewers, we’re willing to suspend disbelief as long as there aren’t two conflicting rules within the same fictional world. Throughout the seven years of “Buffy,” the mix of science and magic never took me out of the story — and indeed, fantasy elements often worked as metaphors applicable to the science-based world. Same goes for “Star Wars”: The fantasy elements don’t hurt the sci-fi elements as long as it follows its internal logic.

More “Star Wars on Trial” essays: (Part 1) (Part 3) (Part 4)