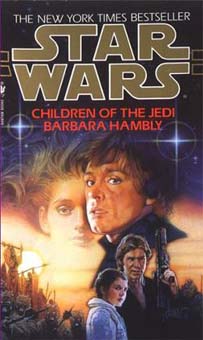

“Children of the Jedi” (1995) is a long and challenging read that I wouldn’t recommend to casual “Star Wars” fans, but it has rewards and trivial curiosities for the die-hards. Barbara Hambly’s debut “Star Wars” novel launches the unofficial “Callista Trilogy” — to be followed by Kevin J. Anderson’s “Darksaber” and her own “Planet of Twilight” — and indeed, Luke’s relationship with his first true love is the emotional core of this trilogy.

Pairing Luke with the love of his life in a story set right after the “Jedi Academy Trilogy” was a daring move by Hambly considering that at this time, one other novel, 1994’s “The Crystal Star,” took place further along the timeline and it made no mention of Callista. On the other hand, it only seems fair that the main character of the saga would get to experience true love. While some fans can’t get past the fact that Callista is trapped in a computer on the Eye of Palpatine, I think it’s a clever way to demonstrate the depth and purity of Luke and Callista’s love. Until she switches bodies with Cray in the final pages, it seems like Callista and Luke will have no future beyond the mission to destroy the ship. When a reader gets to the end and realizes the Luke-and-Callista saga is only just beginning, it’s tempting to dive into “Darksaber” right away.

That having been said, everything else about Luke’s story in “Children of the Jedi” is a tough read. It’s page after page of brainwashed Gamorreans, Tusken Raiders, Jawas and other species tearing up a ship — the Eye of Palpatine — that they’re all trapped on. What’s more, the plot is ridiculous: The Eye of Palpatine is an automated supership programmed to wipe out the hidden Jedi on Belsavis (and, presumably, other hiding Jedi, because it’d be weird to build a superweapon for just one mission). But it makes absolutely no sense that the Eye would have to pick up stormtroopers on various planets just for this mission, nor does it make sense that it accidentally picks up these other species and brainwashes them, nor does it make sense that TIE fighters would partially destroy the Jedi hideout in advance of the Eye’s arrival.

The Han-and-Leia arc is significantly better: Belsavis is an ice planet with populated, fruit-growing rift valleys, and Hambly evocatively brings Plett’s Well to life. It’s fun exploring the fog-shrouded lanes and caves that carve into the cliff walls. Adding an extra layer is the mystery of the title: Leia senses that children of Jedi once lived in those caves. (Hambly did not foresee George Lucas’ prequel portrayal of the Jedi Order’s ban on familial and romantic attachment, and for many years, “Children of the Jedi” stood as apocryphal until Karen Traviss impressively ret-conned it in “Clone Wars: No Prisoners” by exploring a rogue sect of Jedi.)

I also have to credit Hambly for making the destruction of Alderaan a central part of Leia’s internal monologue. Now that she’s the chief of state, Leia has the power to assassinate all the Death Star designers without anyone questioning her. And on some level, she wants to, but of course she doesn’t, because the New Republic doesn’t behave like the Empire. (“Darksaber” will delve further into the various Death Star designers.) It’s also cool to see Leia regularly think back to her time growing up on Alderaan and attending Imperial Court events; for example, she recalls her Aunt Rouge, who schooled her in the ways of proper comportment. Unfortunately, the author doesn’t give us any flashback scenes involving Bail Organa.

Although Mara Jade is a side character here, this is an oddly intriguing book for fans of the character. For one, Mara is angry to discover that there’s another Emperor’s Hand out there — Palpatine’s former concubine, Roganda Ismaren. Roganda is the villain of this piece along with her son, Irek, who has the Magneto-like ability to control droids through the Force. Secondly, it’s interesting to note that there is no romantic tension at all between Mara and Luke in “Children of the Jedi.” It seems clear that Hambly did not have any inkling that Timothy Zahn would later pair up the characters in “Vision of the Future” (heck, maybe even Zahn himself didn’t know at this point).

Thirdly, in a plot thread that the Bantam editors would probably erase if they got a do-over, it’s strongly implied that Mara and Lando are a couple in this book. The Lando-Mara relationship is the most awkwardly written pairing in “Star Wars” lore, making the Anakin-Padme stuff in “Attack of the Clones” look like Shakespeare by comparison. Anderson fumbled the opening in “Champions of the Force” by having Lando act uncharacteristically smitten around Mara, then Hambly implies that they are a couple without telling the story of why Mara changed her mind. Then, in “Vision of the Future,” Mara assures Luke that her relationship with Lando was a ruse as part of their business activities, even though I’m almost certain Hambly did not intend it this way.

Even in 1995, when every new “Star Wars” hardcover was an exciting novelty, I had a hard time getting through “Children of the Jedi.” In a way, it’s bad reputation (2.5 stars out of five on Amazon) is earned. Still, it’s better than the “Jedi Academy Trilogy” at least, and — while it would’ve been great if half the pages had been deleted by a judicious editor — there are some intriguing elements of “Star Wars” lore buried in here for those willing to take the time.